As youth workers, it’s helpful to understand the different models of disability, invisible disabilities and the fundamental right of people to shape their own lives.self-determination. This will help you support disabled young people in the best way possible.

At YACVic, following the guidance from the Youth Disability Advocacy Service (YDAS), we use ‘identity-first language’ - so we say things like, ‘disabled young people’ or ‘disabled person’.

Identity-first language is about pride and autonomy. Many people choose to use this language when talking about themselves. Describing yourself as a disabled person is an example of using identity-first language.

The other way that people may refer to themselves is ‘person-first language’ - for example, saying ‘person with a disability’. This places the focus on the person and de-emphasises disability as a primary identifier.

Using identity-first or person-first language is a personal choice. If you aren’t sure what someone prefers, just ask!

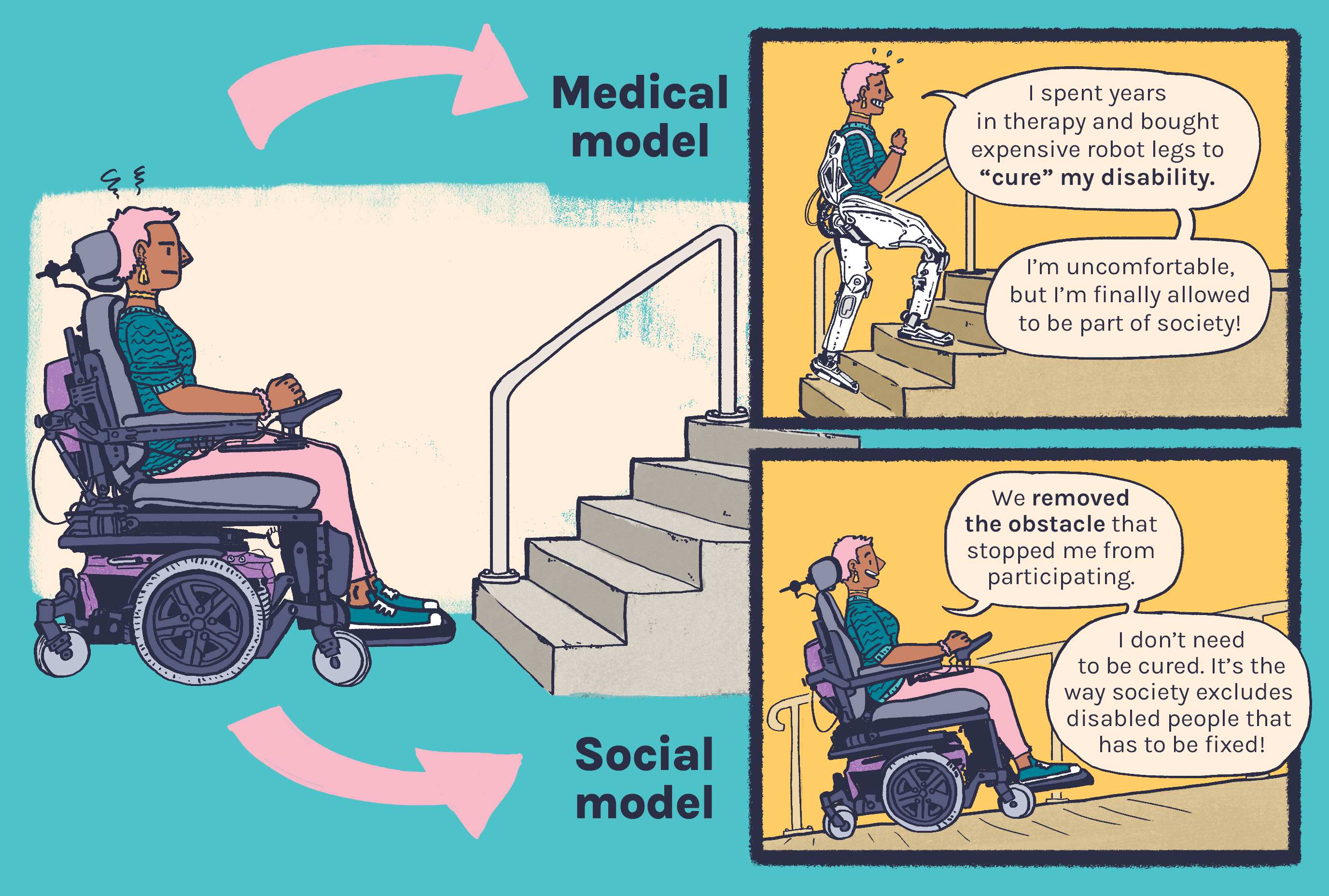

The social model of disability suggests that disability is mainly created when the needs of disabled people are not considered when designing goods, services, and infrastructure. This makes it difficult for many disabled people to participate in society, and to be as independent as non-disabled people.1

The crux of this model is: disabling environments and social barriers create disability.

The social model aims to:

- Highlight the long-standing systemic exclusion and oppression of disabled people.

- Locate disability outside of the individual. It places responsibility on people in power and wider society to create environments that include everyone.1

There are some aspects of individual lived experience that the social model does not address. For example, the impact of chronic pain.2

Illustration with three panels. Panel one shows a person in a wheelchair facing a flight of stairs. There is an arrow pointing to the second panel labelled 'medical model', and an arrow pointing to the third panel labelled 'social model'.

The second panel ('medical model') shows the person wearing a set of bionic legs, and exerting themselves to walk up the stairs. A speech bubble says: “I spent years in therapy and bought expensive robot legs to “cure” my disability. I’m uncomfortable but I’m finally allowed to be part of society!”

The third panel ('social model') shows the person smiling and driving their wheelchair up a ramp. A speech bubble says: “We removed the obstacle that stopped me from participation. I don’t need to be cured. It’s the ways society excludes disabled people that has to be fixed!”

The human rights model of disability is based on the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which recognises disabled people as rights-holders with decision-making capacity and personal agency.1

The human rights model:

- Values disability as a part of natural human diversity, and does not seek to change or 'cure' disabled people.3

- Positions governments and people in power to remove barriers that exclude disabled people.2

- Focuses on the individual lived experience of disabled people.4

The social and human rights models of disability are becoming more widely used models when thinking about disability. They are much more human-focused, involving the rights of disabled people and focusing on the disabling aspects of society.4

These approaches are the best practice models. Think about them as you work alongside and support the self-determination of disabled young people.

The medical model of disability is the oldest and most prevalent model of disability.1 The medical model views non-disabled people as the norm, and disabled people as requiring treatment to ‘cure’ their impairments.4 This model perpetuates narratives of deficiency, tragedy, and helplessness, that contributes to continuing the discrimination (ableism) stigma, and exclusion of disabled people.1

The charitable model of disability is closely tied with the medical model and is the most commonly referred to.3

The charitable model portrays disabled people as helpless and unable to do things for themselves. This model centres a narrative of tragedy: where disabled people are victims of their disability and reliant on able-bodied people to support them.2

While charities offer vital support, traditional fundraising has commonly emphasised the helplessness of disabled people, rather than promoting autonomy, independence and rights.2 This model is often adopted by mainstream media.

These models are examples of unhelpful ways of thinking about disability. They are outdated, and perpetuate stigma and exclusion of disabled people. It’s still important to be informed of these models so you can be critical and aware of these in your practice.

♫ Upbeat instrumental music plays in background ♫

Bethany, co-designer: The Together Project is a project that's looking at helping youth workers build a more accessible and inclusive environment for youth with a disability.

Sebastian, Project Officer: At the moment, if you study youth work, you don't necessarily learn anything about disability, even thought one in five Australians has a disability.

Campbell, co-designer: The Together Project kind of works to break down those barriers and break down those walls for youth workers.

Stella, co-designer: We've done workshops, both in metropolitan Melbourne and also in regional Victoria.

Jessica, participant: I've really enjoyed this program, it's short and sweet but it's the essentials. And it gives us a good foundation.

Bethany, co-designer: One of the really good parts of the workshop is this program has been designed by young people with a disability.

Daniel, participant: So instead of learning from a teacher or a lecturer who is teaching from a textbook, these people actually have life experience.

Sebastian: So the workshops are just a starting point. We wanna put access and inclusion on the agenda. We want participants to go away having this at the front of their minds and to have this guide their actions. To make sure that, with all their work, they're considering how they can be actively inclusive so that young people with disability can access the same services as everybody else.

Daniel: Using this literature that we've been given today will be hopefully life changing for a lot of people.

Sebastian: It really is about just making small, realistic, achievable steps towards access and inclusion.

Stella: I think we've definitely addressed the things that we wanted to. And now, they just have to go out and do it!

- Check out the YDAS Together training for a comprehensive introduction to disability awareness. This training will give you skills and tools to help you include disabled young people.

- Disability Advocacy Resource Unit (DARU) also have a wide range of free resources, modules, and courses that support inclusion and awareness.

An invisible disability is a disability that may not be visible at first glance. It could be something like chronic pain, mental illness, or a cognitive impairment. It’s estimated that 80% of disabilities are invisible.5

Living with an invisible disability comes with unique challenges that others may not consider.

Young people with invisible disabilities are frequently faced with a lack of support and scrutiny over the validity of their disability.5 For example:

- Struggling to get accessible seats on buses and trains which are signposted as being only for people with physical disabilities.

- Difficulty advocating to doctors and other adults to get support.1

Also - invisible disabilities are not always invisible! They often just appear different to expectations of what physical disability is ‘supposed’ to look like.5

In addition to mobility aids and assistive technologies, the symbol of a sunflower is often used by those with an invisible disability to signify to others that they're disabled.

A photo of a sunflower lanyard, which a person with a non-visible disability may wear.

You can’t always tell when someone is disabled and you shouldn’t assume. When you have standard procedures in place, you ensure all young people you work with are supported.5 An example of this is using an 'Access Needs Form' when beginning work with a new young person.

Having existing knowledge and training on different disabilities is valuable, but don’t assume anything about a young person’s disability. Instead:

- communicate directly with the young person, and

- work collaboratively to find ways to best support them.1

Individualised and self-determined support will increase positive outcomes for the young person and improve their overall experience of your program or event.

Key takeaways

- Provide access needs forms as standard practice when starting work with all young people.

- Provide periodic follow-up access need forms as disabilities and/or access needs can change.

- Receive training in disability youth awareness, accessibility, and inclusion. For example, YDAS’ Together Training.

- Communicate directly with the individual young person – don't make assumptions about what they might need or want.

- If funding is an issue, don’t be afraid to get creative and work with the young person to find a solution that works for them.

Self-determination means disabled young people are in control of the important decisions in their lives. This can include setting their own goals, and developing skills to be able to self-advocate for their wants and needs.

This does not mean they have to do everything for themselves, but rather they make their own decisions and shape their lives in the way they want.6

Self-determination has been shown to improve wellbeing and quality of life. It allows disabled young people to develop independence and confidence in their education, employment, and communities.7

A photo of a girl standing with boxing gloves on, smiling.

Those that work alongside disabled young people should encourage self-determination and opportunities to build skills that develop self-determination wherever possible.7

Having open conversations with disabled young people about their interests, goals, and aspirations is a good way to start.6 To do this, create an environment where young people feel safe to share their thoughts and ideas.7

Working collaboratively is also central to this process – the young person should lead the work and make the big decisions.7 The youth worker’s role is to ensure the young person has access to necessary information, and support them to develop a plan to achieve their goals.

Key takeaways

- Start by asking - have an open conversation with the disabled young person about their goals and aspirations.

- Develop a plan together - what are the steps involved in achieving their goals and aspirations?

- Be proactive about checking in and provide support where needed.

Other resources

- Human Rights Law Centre’s Victorian Human Rights Charter Advocacy Guides has a specific section on Victorians with a disability, and how you can work together to advocate for their human rights.

- YDAS’ Map Your Future is a great resource for disabled young people to set and achieve their goals.

- Antoine, S., Moller, A., & Wotherspoon, N. (2023). The intersection of youth and disability: Disabled young people’s experiences of violence, abuse, neglect, and exploitation in Victoria. Youth Disability Advocacy Service (YDAS), Melbourne, Victoria, pp. 1–86. https://www.yacvic.org.au/assets/Uploads/YDAS-DRC-Submission.pdf

- Oliver, M. (2013). The social model of disability: thirty years on. Disability & Society, 28(7), 1024–1026.

- Disability Advocacy Resource Unit. (2017, May 9). Shifting models of thinking. Disability Advocacy Resource Unit (DARU). https://www.daru.org.au/what-is-advocacy/shifting-models-of-thinking

- Youth Disability Advocacy Service. (2023). Four models of disability, Access and Inclusion. Youth Disability Advocacy Service. https://www.yacvic.org.au/ydas/resources-and-training/together-2/values-and-ideas/two-models-of-disability/

- Hidden Disabilities Sunflower. (2023). What is a hidden disability? Hidden Disabilities Sunflower Australia. https://hdsunflower.com/au/what-is-a-hidden-disability

- Lindsay S, Kosareva P, Sukhai M, Thomson N, Stinson J. Online Self-Determination Toolkit for Youth With Disabilities: Protocol for a Mixed Methods Evaluation Study. JMIR Research Protocols. 2021;10(1):e20463. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/20463

- Watson J, Frawley P. Engaging children with disability in supported decision making. Australian Institute of Family Studies. Published 2023. https://aifs.gov.au/resources/short-articles/engaging-children-disability-supported-decision-making

Related Topics

YACVic acknowledges the incredible leadership of YDAS, and we encourage you to check out their resources and trainings for yourself and your organisation.